Mit 6858 Computer Systems Security Fall 2014 Review

Topics

For supply chain executives, the early years of the 21st century have been notable for major supply concatenation disruptions that take highlighted vulnerabilities for individual companies and for unabridged industries globally. In addition to taking many lives, the Japanese seismic sea wave in 2011 left the world motorcar industry reeling for several months. Thailand'southward 2011 floods affected the supply chains of computer manufacturers dependent on hard disks and of Japanese car companies with plants in Thailand. The 2010 eruption of a volcano in Iceland disrupted millions of air travelers and affected fourth dimension-sensitive air shipments.

Today'southward managers know that they need to protect their supply chains from serious and costly disruptions, only the most obvious solutions — increasing inventory, calculation capacity at different locations and having multiple suppliers — undermine efforts to better supply concatenation toll efficiency. Surveys have shown that while managers appreciate the impact of supply concatenation disruptions, they have done very little to prevent such incidents or mitigate their impacts.1 This is because solutions to reduce risk mean little unless they are weighed against supply concatenation cost efficiency. Afterward all, fiscal performance is what pays the bills.

Supply Chain Efficiency vs. Gamble Reduction

Supply chain efficiency, which is directed at improving a visitor's financial functioning, is different from supply chain resilience, whose goal is risk reduction. Although both crave dealing with risks, recurrent risks (such every bit demand fluctuations that managers must deal with in supply chains) require companies to focus on efficiency in improving the fashion they match supply and demand, while disruptive risks require companies to build resilience despite additional cost.

Disruptive risks tend to take a domino effect on the supply chain: An bear upon in one expanse — for example, a fire in a supply plant — ripples into other areas. Such a risk can't be addressed past holding additional parts inventory without a substantial loss in toll efficiency. Past contrast, recurrent risks such as demand fluctuations or supply delays tend to be independent. They can ordinarily exist covered by expert supply chain management practices, such as having the correct inventory in the right place.

Since the mid-1990s, managers take get much better at managing global supply bondage and mitigating recurrent supply concatenation risks through improved planning and execution. As a outcome, the 1990s saw big jumps in supply chain toll efficiency. Nevertheless, reliance on sole-source suppliers, common parts and centralized inventories has left supply chains more vulnerable to disruptive risks. Although sourcing from or outsourcing to afar low-price locations and eliminating excess chapters and redundant suppliers may make supply chains more cost efficient in the short term, such deportment also make these supply chains more vulnerable to disruptions — with potentially damaging financial implications when they occur. Low-toll offshore suppliers with long pb times go out companies vulnerable to long periods of shutdown when particular locations or transportation routes feel problems.

How should executives lower their supply concatenation's exposure to disruptive risks without giving up hard-earned gains in financial operation from improved supply chain cost efficiency? Disruptions are commonly well across a manager'southward control, and dealing with them can affect a supply chain's cost efficiency. To avoid increased costs, a director might choose to practice zippo to prepare for "acts of God" or forcefulness majeure. The culling is to reconfigure supply bondage to better handle disruptions, while accepting whatsoever effects on cost efficiency. In many instances, it is not an all-or-nothing suggestion. Companies could elect to deploy different strategies in different settings or at unlike times. (See "About the Research.")

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that tin can assist yous lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Cheers for signing upwardly

Privacy Policy

In an earlier MIT Sloan Management Review article,2 we considered different supply concatenation configurations for risk and performance. We discussed different mitigation strategies that companies could tailor to the type and level of chance they faced. To implement those strategies we notice, broadly speaking, that today's managers have ii choices for achieving lower risk in the supply chain: They tin can reduce risk while besides improving supply chain efficiency — a "win-win" – or they tin can reduce risk while limiting the impact on supply chain cost efficiency.

Reduce the Risk and Improve the Operation

Supply bondage often incorporate a huge number of products or commodities that are sourced, manufactured or stored in multiple locations, thus resulting in complexity. Complication can hateful reduced efficiency every bit managers struggle with the day-to-24-hour interval risks of delays and fluctuations, and it can pb to increased take a chance of disruption, in which dependencies between products can bring everything to a halt. Controlling the amount of complexity tin therefore lead to college price efficiency and reduced take chances, which is a win-win. Permit'south begin by considering take chances.

Managers tin can reduce risk by designing supply chains to contain adventure rather than allow it to spread through the entire supply concatenation. The design of an oil tanker provides a plumbing fixtures example of how good design choices tin reduce fragility. Early on oil tankers stored liquid cargo in two iron tanks linked together by pipes. Merely having two big storage tanks caused major stability problems; as the oil sloshed from one side of the vessel to the other, tanker ships were decumbent to capsizing. The solution was to design tankers with more compartments. Although such ships were more than expensive to build, this approach eliminated the stability problem.

In a similar vein, executives need to ensure that the affect of supply chain disruptions can be contained within a portion of the supply concatenation.3 Having a single supply chain for the entire company is analogous to having an oil tanker with a single cargo hold: It may exist cost effective in the short run, merely one small trouble can cause major damage.

In full general, containment strategies are aimed at limiting the touch of a disruption to one part of the supply chain (in other words, like i hold in an oil tanker). For instance, a car company might have multiple supply sources for common parts or restrict the number of common parts across unlike car models as a way to reduce the impact of a possible recall or a parts shortage. We suggest 2 strategies for reducing supply chain fragility through containment while simultaneously improving financial functioning: (ane) segmenting the supply concatenation or (2) regionalizing the supply chain. In add-on, we suggest how companies can blueprint concern continuity plans or reply to confusing risk incidents using these strategies.

1. Segment the supply chain.

The story of Zara'south success using responsive sourcing from Europe is well known. Less known is the fact that as early as 2006, Zara, a clothing and accessories retailer based in Arteixo, Kingdom of spain, was getting one-half its merchandise from low-cost suppliers in Turkey and Asia.four What motivated this motion to lower-cost countries? As Zara grew, it realized that producing everything in high-cost locations in Europe was not helping increase margins. Although it made sense to source the trendiest items from European factories that could produce them rapidly for European customers, bones items such as white T-shirts did not justify the same level of responsiveness. So Zara began to source some products from lower-cost locations. In doing so, it also reduced the impact of a potential disruption, since not all items would be affected by a disruption in i geographic area.

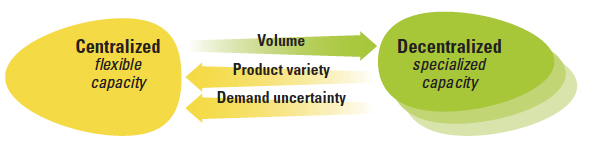

Big companies can segment their supply chains to improve profits and reduce supply concatenation fragility. For high-volume commodity items with low need uncertainty, the supply chain should have specialized and decentralized capacity. For its fast-moving basic products (typically, low margin), information technology may be worthwhile to do what Zara does: Source from multiple low-price suppliers. (See "Segmenting the Supply Concatenation.") This reduces price while also reducing the affect of a disruption at any single location, because other suppliers are producing the same item. For low-volume products with loftier demand uncertainty (typically, high margin), companies can take a different approach and continue supply chains flexible, with capacity that is centralized to aggregate demand.

The supply chain can be segmented using volume, product variety and need uncertainty. Higher volume favors decentralizing (with more segments), as in that location is fiddling loss in economies of scale. But significant product variety often goes manus-in-hand with depression volumes of the individual products, then centralizing (with fewer segments) is needed. High need uncertainty also requires centralizing to achieve reasonable levels of performance.

Even when production is centralized, the supply chain needs to be flexible to avoid concentrating risk in a single plant or production line. For example, to protect itself against supply disruption, Zara's European operations are set up so that multiple facilities can produce even low-volume items. Practically speaking, this level of segmentation may not be feasible for small-scale companies lacking sufficient scale.

W.W. Grainger Inc., which distributes industrial supplies to businesses, offers another case of reducing chance by segmenting the supply concatenation. The Lake Forest, Illinois-based company has about 400 stores in the The states. In an endeavour to reduce transportation costs, it keeps its fastest-moving products at the stores and at 9 distribution centers. Nevertheless, the slower-moving items are warehoused at a distribution center in Chicago. This partitioning reduces fragility by isolating the impact of disruptions and creating supply backups. Similarly, Amazon.com Inc. has expanded its number of U.S. distribution centers to exist closer to consumers. Similar Grainger, Amazon maintains inventory of its almost pop items in the distribution centers and tends to hold slow-moving items more centrally.

Supply chains can and should evolve over time in response to product life cycles or experience with a new market.v Early on, when sales are low and need uncertainty is high, managers can pool recurrent adventure and minimize supply chain costs by centralizing capacity. But, equally sales increase and dubiousness declines, capacity can be decentralized to become more responsive to local markets and reduce the risk of disruption.

In addition to separating products with different take chances characteristics, managers should consider treating the more as well as the less predictable aspects of demand separately. They should view such an approach not only as a mode to cut costs but, more than chiefly, every bit a mode to lessen the run a risk of disruption. Some utility companies use this arroyo. They employ low-cost coal-fired power plants to handle predictable base demand, and they then shift to higher-cost gas- and oil-fired power plants to handle uncertain superlative demand. Having two or more than sources of supply reduces the impact of disruption risk from a unmarried product facility.

ii. Regionalize the supply chain.

Containing the impact of a disruption can also mean regionalizing supply bondage then that the bear upon of losing supply from a plant is contained within the region. Japanese automakers didn't follow this approach and paid a heavy price when the 2011 tsunami hitting. Plants worldwide were affected by a shortage of parts that could be sourced just from facilities in the tsunami-affected regions of Japan.

Since rising fuel prices increase transportation costs, regionalizing supply chains provides an opportunity to lower distribution costs while likewise reducing risks in global supply bondage. During periods of low transportation costs, global supply chains attempted to minimize costs by locating production where the costs were the everyman. Yet, as events like the Japanese earthquake showed, this arroyo can hateful increased fragility, every bit the impact of any disruption tin can be felt across the entire supply chain.

Equally transportation costs rise, global supply chains may be replaced by regional supply chains. Like those of other companies, consumer goods producer Procter & Hazard Co.'due south supply chains were designed in the 1980s and 1990s, when oil was virtually $10 a barrel. At the time, P&M designed a more centralized production network with the primary objective of keeping upper-case letter spending and inventories to a minimum. With oil prices much college today, the most cost-effective network is more than distributed, with multiple plants even within a unmarried country like China.half dozen

In improver, growing demand in emerging economies has caused some companies, such as London-based Diageo plc, the globe'south largest distiller, to rethink their production and distribution networks from the ground up. In an effort to profitably increase its market share, Diageo is abandoning its global supply chain in favor of regional supply chains with local sourcing and distribution, often organized at a country level.7 Regionalizing ofttimes helps companies reduce costs while also containing the impact of disruptive events such as natural disasters or geopolitical flare-ups to a particular region. In the event that there is a problem, affected markets can be served temporarily by supply bondage in neighboring regions.

In many production categories, companies are deciding to regionalize their supply bondage to serve fifty-fifty developed markets. For instance, Polaris Industries, a maker of all-terrain vehicles based in Medina, Minnesota, considered locating a plant in China to serve its market in the southern The states. But it ultimately decided to locate the establish in Mexico to save on transportation costs and allow for greater responsiveness. Similarly, some Chinese and Indian textile manufacturers are setting upward plants in the United states despite the low labor costs at dwelling. Although companies determine to regionalize supply chains to achieve lower costs, they too consequently "de-risk" their overall supply chain.

Managers need to reply to supply chain disruption incidents when these do occur, just how they respond will depend on how they accept configured the supply chain. Researchers have identified three stages of response:eight (ane) detecting the disruption, (2) designing a solution or selecting a predesigned solution and (3) deploying the solution.

Given that many companies have invested in a diversity of information engineering systems for monitoring material flows (such as delivery and sales) and information flows (such as need forecasts, production schedules, inventory level and information about quality) to ensure performance and manage recurrent risks, another win-win strategy is to leverage these systems to contain the impact of supply chain disruption incidents by ensuring the company can react quickly to such incidents. Such IT systems can be a win-win: They can reduce the bear upon of hazard incidents by enabling a quicker response by screening for possible disruptions. To leverage the do good further, the time required to pattern supply bondage tin can be significantly shortened if a company and its partners can develop contingent recovery plans for unlike types of disruptions in advance. Li & Fung Ltd., a Hong Kong-based contract manufacturing company, has a variety of contingent supply plans that enable information technology to shift production from a supplier in one state to another supplier in a dissimilar state.

Building on the two containment strategies described above, detection, design and deployment become simpler and faster when the supply chain is segmented or regionalized. When supply chains are regionalized, the design fourth dimension and necessary deployment time for backup supply can be reduced. Whereas a supply chain focused on improvements in price efficiency may find itself without a backup in the event of a disruption, segmented or regionalized supply chains are more than likely to have backup sources for critical parts or bolt. Thus, managers with segmented and regionalized supply chains tin can design and deploy solutions fairly quickly in the event of a disruption. For instance, the International Federation of Blood-red Cross and Red Crescent Societies holds inventories of vital goods in four geographically separate logistics centers to facilitate responses to earthquakes and other humanitarian disasters in any part of the globe.9 While maintaining the same inventory in multiple locations may seem improvident, a less-distributed model would not exist able to reply as apace or efficiently. What'south more than, the supply chain itself is more robust — in case 1 of the logistics centers suffers a cataclysm.

Reduce Risk While Limiting the Impact on Toll Efficiency

In many instances, reducing disruption risk involves higher costs. In fact, the reason executives are reluctant to deal with supply chain risk comes from the perception that risk reduction will reduce cost efficiency significantly. Nevertheless, managers can exercise much to ensure that loss of cost efficiency is minimal while the risk reduction is substantial past avoiding excessive concentration of resources similar suppliers or chapters. And nudging merchandise-offs in favor of less concentration by overestimating the probability of disruptions tin can be much better in the long run compared to underestimating or ignoring the likelihood of disruptions.

ane. Reduce the concentration of resources.

A direct consequence of making global supply chains more efficient and lean has been the increase in fragility. The billions of dollars of lost sales and costs that Toyota Motor Corp. incurred in the wake of its product recalls in 2010 were a straight outcome of a supply chain that relied on using a single part, sourced from one supplier, in many car models. Although using a common part helped Toyota reduce costs, it became the supply chain's Achilles' heel.

Companies ofttimes manage their 24-hour interval-to-day recurrent risks past "pooling" inventory and capacity past having fewer distribution centers or plants or by having common parts. More pooling reduces the supply chain cost incurred to mitigate recurrent (as opposed to disruptive) risks; the greater the total corporeality of pooling of parts and capacity, the greater the total do good. It is important to realize, however, that pooling provides diminishing marginal benefits when dealing with recurrent risk.10 Simultaneously, increased pooling can brand the overall supply concatenation more vulnerable to disruption risk. As the Toyota instance illustrates, the use of common parts produced by a single supplier in many models tin can magnify the impact of a quality-related disruption.

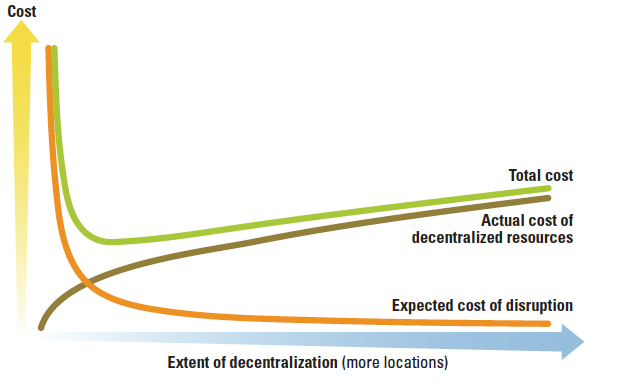

Should managers seek to make their supply chains more lean and efficient by concentrating common parts and single suppliers, or should they seek to reduce disruptions and dorsum off from trying to be more lean and efficient? To answer this question, it is important to recognize that pooling recurrent risks past, say, reducing the number of distribution centers, has diminishing marginal returns for supply chain performance while increasing the supply chain fragility and hence the boosted hazard of disruptions. When an auto manufacturer has no mutual parts any across unlike models of cars, building some degree of commonality offers meaning benefits. But the marginal benefits grow smaller every bit more than parts are fabricated common. Conversely, going from 1 distribution center to ii can dramatically reduce fragility without significantly losing too many of the benefits of pooling recurrent risks; this is especially true for large companies.11 (Run across "Decentralization and Costs.") It is therefore possible to achieve an optimal point in pooling resources by manner of parts commonality or fewer plants or distribution centers. This keeps recurrent risks low by pooling the resource and besides keeps fragility of the supply chain low by non taking pooling to extremes.

The actual toll of a resource goes up equally a consequence of having multiple warehouses requiring more inventory, while the expected impact of a disruption goes downward. Going from right to left, the total price decreases every bit nosotros centralize or pool the resource, but the toll jumps upward as nosotros centralize beyond a certain point. Thus, using a single supplier or a unmarried warehouse adds cost.

Thus, executives need to go along in mind that dealing with recurrent risks in the supply chain shifts the balance toward more centralizing of resources, pooling and commonality of parts, whereas dealing with rare confusing risks pushes the balance in the opposite management. Finding the right residuum for recurrent risks requires evaluating the costs of increasing or decreasing inventory, capacity, flexibility, responsiveness and adequacy, and centralizing or decentralizing inventory and/or capacity.12 Yet, managing disruptive risks will require designing supply bondage where the resource in question (say, parts inventory or the number of suppliers) is never completely centralized. This is why companies such as Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. always aim to have at to the lowest degree two suppliers, fifty-fifty if the 2d 1 provides only twenty% of the book.13

The implications of these principles are obvious. When the cost of building a found or a distribution centre is low, having multiple facilities in dissimilar locations reduces the supply chain's risks without significantly increasing costs. In full general, this is true when in that location are no pregnant economies of scale in having a large plant or when having inventory in the distribution center is relatively cheap. Merely even when economies of calibration are pregnant enough to warrant having a single source to address recurrent risks or the cost of maintaining inventory is high, extreme concentration should still exist avoided due to the potential touch on of disruptive risks. Ignoring or underestimating the possibility of disruption tin be very expensive in the long run, as it means having all of your eggs in one basket. Having even two baskets, while adding to the price, greatly reduces fragility. Each boosted basket typically has a larger marginal cost, while decreasing fragility by smaller marginal amounts. Yet, having many more than two baskets would be overkill is most cases: Information technology would cost significantly more and wouldn't reduce fragility much.

2. Nudge trade-offs in favor of reducing risk past overestimating the likelihood of a disruption.

In a well-documented case of supply chain disruption that took place in 2000, a burn in a Philips Electronics establish in New Mexico interrupted the supply of disquisitional cellphone fries to 2 major customers: Ericsson and Nokia. While Nokia was able to observe an alternate supply source in three days, Ericsson lost about a month of production. Due to component shortages, its mobile phone division suffered a $200 million loss during that period. Nokia's ability to regroup came at an upfront price, but it paid off in terms of less disruption.

Realistically, information technology is impossible to gauge the probability of a plant burn down, the bankruptcy of a supplier or a faulty component. Compounding the problem is the human tendency to underestimate the probability of rare events the further removed we are from the fourth dimension such events last occurred.fourteen Thus, supply chain designers and managers often underestimate disruptive take chances when thinking most mitigation strategies. Traditional chance cess comprises estimating the likelihood and the expected impact of an incident.15 In the context of disruptive risks, information technology is hard to come up upwards with good or even credible estimates. For example, there was no reasonable way for an automaker like Toyota to judge the probability of a part failure or for airlines to anticipate that European airspace would be closed to air traffic.

In such settings, managers have an incentive to underestimate the likelihood of confusing risks by simply ignoring them — thus avoiding the need to deconcentrate resources or make any merchandise-offs at all. After all, preparing for a possible disruptive risk incident requires upfront investment in gamble mitigation. That makes it attractive for managers with fixed budgets to underestimate or even completely ignore the likelihood of a disruption.

Just underestimating confusing risks, for instance, past completely ignoring them, is a dangerous bet. Our inquiry using analytical models and simulation constitute that underestimating the likelihood of a confusing event is far more expensive in the long run than overestimating the likelihood.16 In the effect of a disruption, the loss incurred generally overwhelms whatever savings from not investing in take a chance mitigation strategies. This was conspicuously the case for Ericsson: Whatsoever savings it might take generated from having a single supplier were overwhelmed by the losses from the constitute shutdown. In contrast, strategies designed to deal with disruption take a chance (such equally having multiple suppliers) compensate for the upfront cost to some extent by providing some benefits even in the context of recurrent hazard (for case, supply can be shifted from one supplier to another as regional need or commutation rates shift). To exist sure, investment in additional facilities to mitigate the issue of rare disruptions is a real cost, while the savings from avoided costs of disruptions are hypothetical until a disruption occurs. All the same, given that fifty-fifty rare events will actually occur, the average costs from disruptions are typically much larger than whatsoever savings from fugitive upfront investments. Overinvesting in protection against disruptions may be more economic in the long run than non doing enough. (Come across "Overestimating Risk Results in Improve Decisions.")

Underestimating the likelihood of a disruption results in a larger increase in long-run cost compared to overestimating the likelihood of disruption. However, small misestimates have very small consequences.

Moreover, one doesn't need to judge the hazard of disruption with corking precision. For a typical supply concatenation, we found that the full expected cost of a robust supply chain is non very sensitive to small errors in estimating the likelihood of disruption. In our simulations, an mistake of up to 50% in estimating disruption probability in either direction resulted in less than a two% increase in full costs stemming from disruptive risk incidents over the long run. Large costs from hereafter disruptions can be avoided as long as the risk of disruption is not completely ignored. And so rough estimates of disruption risk are sufficient, and overestimating is better than underestimating. This noesis should help managers make better merchandise-offs between reducing the take a chance of disruption and accepting reduced cost efficiency.

Senior managers cannot ignore disruption risk management because effective solutions are unlikely to exist identified and implemented at the local level. Executives should carefully stress test their supply chains to sympathize where there are risks of disruption.17 The goal of this idea exercise is to identify not the probability of disruption merely the potential sources of disruption. If no risk mitigation strategies are in place for a particular source of disruption, a disruption probability of zip has effectively been causeless. This pregnant underestimation can be very expensive in the long run and should be avoided if at all possible. Information technology is oft cheaper in the long run to assume some arbitrary only positive probability of disruption rather than to ignore information technology.

For big companies in particular, building resilience is ofttimes relatively inexpensive, and in many cases information technology can exist washed without increasing costs. Segmenting the supply concatenation based on product volume, variety and need doubt not only increases profits; it besides improves the power of the supply chain to contain the affect of a disruption. Similarly, for many products, peculiarly those with high transportation costs, regionalizing the supply chain both reduces cost and improves supply concatenation resilience. But even when implementing a take a chance mitigation strategy seems expensive, it is important to call up that in the long run, doing nothing can be much more than plush.

To be sure, overestimating the probability of disruption requires senior managers to overcome ii challenges. Kickoff, they must be willing to invest in additional supply concatenation resilience even though the benefits may not follow for a long fourth dimension. Since ignoring disruption is always cheaper in the short term, companies must be willing to blot the additional costs and maintain their delivery to the additional investment (such every bit a backup supplier) even when no disruption occurs for a few years.

The 2nd challenge relates to how supply chain resilience gets measured and implemented. A visitor'southward leadership must convince the global supply concatenation of the benefits of overestimating the probability of disruption and must be able to implement global (as opposed to local) mechanisms to bargain with disruption. Building a reliable backup source at a high-cost location may make sense globally, even when each location may prefer to source from the lowest-price location. To the extent that the deconcentrated resources can be deployed in segmented or regionalized supply chains, the executive's job of explaining any increase in local costs is rendered easier through a subtract in global costs.

References

1. C.S. Tang, "Robust Strategies for Mitigating Supply Concatenation Disruptions," International Periodical of Logistics Research and Applications 9, no. 1 (2006): 33-45.

2. South. Chopra and Chiliad.South. Sodhi, "Managing Gamble to Avoid Supply-Concatenation Breakdown," MIT Sloan Management Review 46, no. 1(autumn 2004): 53-61.

3. M. Lim, A. Bassamboo, S. Chopra and M.South. Daskin. "Flexibility and Fragility: Apply of Chaining Strategies in the Presence of Disruption Risks," Northwestern University research report, 2010.

4. Run into K. Capell, "Fashion Conqueror," BusinessWeek, Sept. 4, 2006.

v. R.H. Hayes and S.C. Wheelwright, "Link Manufacturing Process and Product Life Cycles," Harvard Business organisation Review 57, no. 1 (January-February 1979): 133-40.

vi. J. Birchall and E. Rigby, "Oil Costs Force P&G to Rethink Supply Network," Financial Times, June 26, 2008.

seven. L. Lucas, "Diageo Overhauls Its Supply Chain," Fiscal Times, March xi, 2013. In the by, Diageo largely sold a few premium brands globally (such as premium Scotch whiskey). These were sourced from a central location and distributed globally. As Diageo has grown in emerging markets, it has started selling many other products locally. While the sourcing for Scotch whiskey cannot be decentralized for obvious reasons, Diageo has worked hard to locally source every bit many products equally possible, creating a more than regional supply chain.

8. M.Due south. Sodhi and C.S.Tang, "Managing Supply Concatenation Risk" (New York: Springer, 2012), chap. 5.

9. Run into, for instance, L.N. Van Wassenhove, "Humanitarian Aid Logistics: Supply Concatenation Management in High Gear," Journal of the Operational Inquiry Society 57, no. 5 (May 2006): 475-489.

ten. Chopra and Sodhi, "Managing Risk to Avoid Supply-Concatenation Breakdown."

11. Actual costs go up with the square root of the number of pools of resource, while expected costs of disruption go down as the inverse of the number of pools.

12. Chopra and Sodhi, "Managing Take a chance to Avert Supply-Chain Breakup."

13. G. Sodhi and S. Lee, "An Analysis of Sources of Risk in the Consumer Electronics Industry," Journal of the Operational Research Society 58, no. 11 (November 2007): 1430-1439.

14. N.N. Taleb, "The Black Swan: The Affect of the Highly Improbable" (New York: Random House, 2007).

15. Sodhi and Tang, "Managing Supply Chain Chance," chap. 3.

sixteen. Thou.One thousand. Lim, A. Bassamboo, Southward. Chopra and M.S. Daskin, "Facility Location Decisions With Random Disruptions and Imperfect Interpretation," Manufacturing & Service Operations Management xv, no. 2 (spring 2013): 239-249; and B. Tomlin, "On the Value of Mitigation and Contingency Strategies for Managing Supply Concatenation Disruption Risk," Management Science 52, issue 5 (May 2006): 639-657. In a dissimilar setting, Tomlin (2006) observed results similar to Lim et al. (2013) from misestimating the duration of a disruption. He found that underestimating the duration of a disruption typically led to significantly larger increases in cost than overestimating the duration of a disruption.

17. Chopra and Sodhi, "Managing Gamble to Avoid Supply-Chain Breakdown."

Source: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/reducing-the-risk-of-supply-chain-disruptions/

0 Response to "Mit 6858 Computer Systems Security Fall 2014 Review"

Post a Comment